Figuring out who made what, and when, is an important part of the collecting life for me. Last month, I made the pilgrimage north to Lehigh County, Pennsylvania for Das Awkscht Fest, a three-day party revolving around old  cars and old toys in the normally quiet little town of Macungie. Along with the toy shows and hundreds of jaw-dropping classic cars, the event boasts a huge automotive flea market; rain or shine, row after row of vendors set up and sell just about anything you might possibly need for your Packard or Pontiac or Pierce-Arrow.

cars and old toys in the normally quiet little town of Macungie. Along with the toy shows and hundreds of jaw-dropping classic cars, the event boasts a huge automotive flea market; rain or shine, row after row of vendors set up and sell just about anything you might possibly need for your Packard or Pontiac or Pierce-Arrow.

The night before it all got underway, I had dinner with my friend Ben and his family. Not surprisingly, the talk turned for a time to toys, and we continued a conversation we had started earlier at his house as he gave me a tour of his world-class early plastic toy collection. A year prior, Ben had sold me a five-inch plastic pickup truck after I had shown him a five-inch plastic sedan made by the same company, which I had just scored at the Saturday morning show. Along with the fact that it was mint boxed, what really pushed my button about the sedan was the fact that it was more or less a twin to a similar car I’ve had in my collection for years—a car about which I’ve been able to learn absolutely nothing.

This “mystery” car has a friction motor that has the words “Made in Germany” stamped on the casing, and is based on the Jowett Javelin, a British car made in the late 1940s and early 1950s. I’ve had it for years and had no clue as to its origin or maker. But when Ben told me he had a pickup truck from the same series as the sedan I had just found, he provided a piece of information that advanced things a bit: Although the sedan (like my mystery car) is unmarked either on the toy itself or on the box, the pickup truck is marked “Luxor Made in Holland.” Now we had something to go on, as Luxor was an established (if minor) player among European toy makers in the 1950s. The fact that the “Mechanical Motorcar” series was made by Luxor told me that the maker of my mystery car either copied the Luxor toy, or perhaps inspired the Dutch manufacturer to include a model of the Jowett in its Mechanical Motorcar series.

Ben likes putting together this kind of puzzle as much as I do, which is why I brought all three pieces to show him when I traveled to the Macungie event last month. We examined them and kicked around a few ideas, but in the end, the manufacturer of the mystery car remains—for now—a mystery. But you’d better believe I’m now hunting for Luxor pieces with a passion.

As for the Macungie shows this year, they proved, as usual, to be target-rich environments for me. Early Friday morning, I dug out a late-1940s tinplate Tri-Ang Minic petrol tanker from a plas tic bin that was filled with new-ish action figures and model kits. I asked the seller if he was firm on his $50 price (a bargain, as these often sell for $75 to $100), and he said he was, so I paid up. I took my find back to my car wondering how this English tinplate treasure—in superb original condition—could wind up thrown in with Aragorn and Frodo from The Lord of the Rings. By the way, if you have the February 2012 issue of Antiques Roadshow Insider, check out my feature piece in that issue, “Worthy Competition,” which explores the world of Minics.

tic bin that was filled with new-ish action figures and model kits. I asked the seller if he was firm on his $50 price (a bargain, as these often sell for $75 to $100), and he said he was, so I paid up. I took my find back to my car wondering how this English tinplate treasure—in superb original condition—could wind up thrown in with Aragorn and Frodo from The Lord of the Rings. By the way, if you have the February 2012 issue of Antiques Roadshow Insider, check out my feature piece in that issue, “Worthy Competition,” which explores the world of Minics.

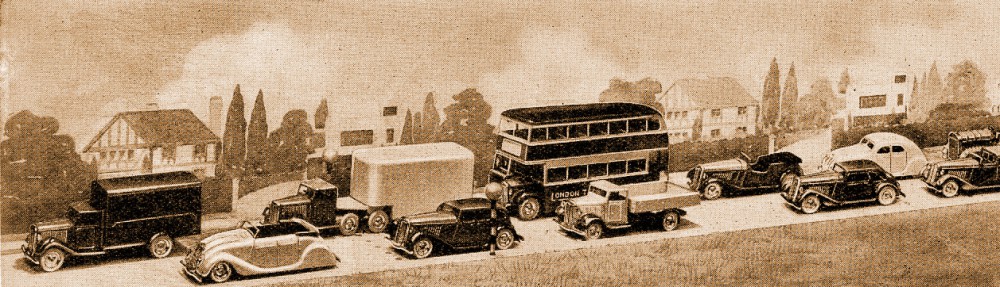

The icing on the cake came on Saturday morning, when I purchased a cardboard garage, made in the 1930s by an Indiana company called Warren Paper Products. These “Built-Rite” buildings are as scarce as hen’s teeth and look terrific when they’re displayed with toy cars of the period. I’ll put this one together and see if my Minic tanker will fit inside.

Douglas R. Kelly has nothing against today’s automakers, but he thinks new cars should come in boxes, for display purposes.

ged) and absolutely screamed early 20th century industrial design. It may not have been love, but I definitely was smitten with this piece of maritime history. The telegraph itself was similar to the one shown at left, although this one is without the stand. (It still sold for almost $300 at a 2011 auction.)

ged) and absolutely screamed early 20th century industrial design. It may not have been love, but I definitely was smitten with this piece of maritime history. The telegraph itself was similar to the one shown at left, although this one is without the stand. (It still sold for almost $300 at a 2011 auction.) still hard to find the good stuff,” he told me. “We’re seeing more aluminum units—usually they’re Japanese made—now than ever before. And in terms of finding telegraphs and binnacles [deck-mounted instrument stands], the price of scrap metal affects us a lot…when the market prices for brass and copper go up, that has a real impact on what we’re able to get.”

still hard to find the good stuff,” he told me. “We’re seeing more aluminum units—usually they’re Japanese made—now than ever before. And in terms of finding telegraphs and binnacles [deck-mounted instrument stands], the price of scrap metal affects us a lot…when the market prices for brass and copper go up, that has a real impact on what we’re able to get.”

burg, Massachusetts-based Irwin Corporation in the early 1950s. It was in excellent original condition and the friction motor worked like a charm. I told him it looks terrific in my collection, and he really seemed to get a kick out of that.

burg, Massachusetts-based Irwin Corporation in the early 1950s. It was in excellent original condition and the friction motor worked like a charm. I told him it looks terrific in my collection, and he really seemed to get a kick out of that. rested in taking the van back in exchange for my purchasing a Tootsietoy sports car kit that I had been eyeing in one of his cases. The kit was an Austin-Healy, made around 1960, and was still on its original blistercard. The kit was more expensive than the Ideal van, and I suggested that I just give him the difference. He didn’t have to accept the deal, of course, as it meant he’d be taking back a damaged item.

rested in taking the van back in exchange for my purchasing a Tootsietoy sports car kit that I had been eyeing in one of his cases. The kit was an Austin-Healy, made around 1960, and was still on its original blistercard. The kit was more expensive than the Ideal van, and I suggested that I just give him the difference. He didn’t have to accept the deal, of course, as it meant he’d be taking back a damaged item.